“Overtourism is complex – careful analysis is required”

by Harold GoodwinProfessor Emeritus and Founding Director of the Responsible Tourism Partnership

Concerns about the negative impacts of tourism are not new. Theilmann has written of the origins of tourism in medieval pilgrimage and argues that pilgrimage “provided an acceptable means for peasants to leave the local community for a time.” (1)

Concern about the unacceptable behaviour of people staying away from home in someone else’s place is not new. Some theological authorities in the Middle Ages and Early Modern period argued t contra peregrinationem concerned about “the unjustified creation of cults, the veneration of unascertained saints, the immoral behaviour of some pilgrims, and different forms of criminal behaviour like robbery, prostitution, fighting, and drunkenness.”(2)

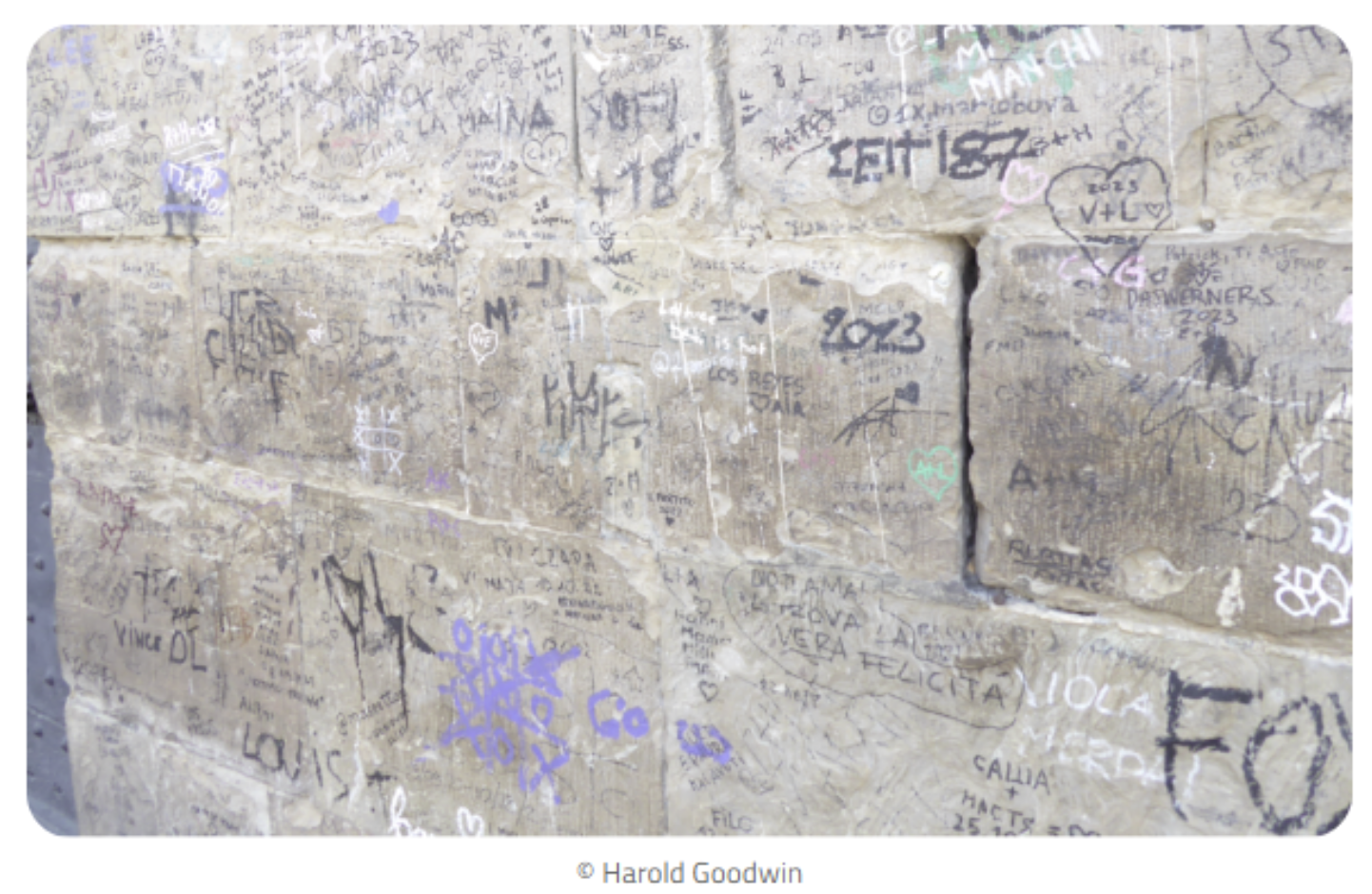

Graffiti has been defacing buildings and caves for centuries. This on the Ponte Vecchio in Florence.

In 1975 Doxey (3) presented his Irridex at the Travel Research Association annual conference. Doxey suggested that how the local community would respond to the experience of tourists arriving in larger numbers over time would begin with a sense of excitement and anticipation, the euphoria stage, followed by apathy, annoyance and antagonism. In 1980 Butler published his Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model (4) which suggests that a tourism area evolves through six predictable stages: exploration, involvement, development, consolidation, stagnation and decline or rejuvenation.

These conceptual models are difficult to apply and are more useful for suggesting the scale and complexity of the challenge than they are as analytical or management tools. Communities rarely speak with one voice. All four of Doxey’s attitudes to tourists are always likely to be present, to a greater or lesser extent. Euphoria, apathy, annoyance and antagonism will be experienced by the same resident on different days and the numbers feeling each of these emotional responses will vary with the season, the extent to which the individual encounters tourists and the behaviours of those tourists.

Attitudes to crowding vary too – we may seek solitude on the beach, while others may enjoy a crowd with fun and games. We may avoid quiet bars and cafes or seek them out, we expect flea markets to be crowded. I used to organise an annual group tour to Prague for Christmas. I ran the last one in 1988 because we did not encounter any Czechs, and Wenceslas Square was crowded with tourists. For me the experience was spoilt but only because I had known it otherwise. Whether or not a destination is spoilt depends on your expectation, it is the gap between the expectation and the experience that creates dissatisfaction.

For the residents, the host community, it is the nature of the impacts that they experience. I do not use Oxford Street in London; I don’t care how many tourists are there. I do care that the South Bank is now dominated by tourists – I no longer go there to walk by the river. I no longer go to London theatres because the audiences are largely not from London or Britain. The visitors too may doubt the performance’s authenticity, because the audience often defines authenticity. The social anthropologists recognise that when strangers enter or peak backstage annoyance and antagonism results, volume is not all that matters.

When I came across a car stopped in the middle of a lane in mid-Wales and four Chinese tourists photographing a sheep, I was charmed. The residents of Kidlington in Oxfordshire were less than charmed when busloads of Chinese and Japanese tourists arrived taking photographs of the houses and knocking on doors to ask for selfies. Kidlington is en route to the shopping village at Bicester (5).

“Overtourism describes destinations where hosts or guests, locals or visitors feel that there are too many visitors and that the quality of life in the area, or the quality of the experience, has deteriorated unacceptably.” (6) The concept was first used in the context of integrated coastal zone management in 2008 and on Twitter in 2012, the issue featured in the 2015 municipal elections in Barcelona and “overtourism” now gets 3.3m hits on Google.

In 2018 overtourism made the shortlist for Oxford Dictionaries’ word of the year. It captures the range of symptoms, overcrowding, housing shortages, changes in the retail offer, and conflicts over social behaviour. It is an umbrella term for a range of symptoms. It arises when tourist arrivals exceed the capacity of the destination to cope with the number of day visitors and overnight tourist, when the Limits of Acceptable Change have been breached. But that limit changes over time, there is rachet effect, each generation of tourists being more tolerant of the crowds, they know no different.

Demand is not the issue arrivals is, rarely does the destination control the ports, airports, road network or railway. Through planning the local authority may be able to control licensed tourist accommodation but destinations are struggling to regulate and manage rentals.

Barcelona has recognised that visitors to the city include Spanish and Catalonian residents, professional and business MICE travellers, students and academics, sports players and fans, families and stag and hen parties, and people visiting their friends and relatives. The visitors are not homogenous, quite the contrary they go to different places and behave in a wide variety of ways, some “fit in” better than others.

Barcelona has recognised that visitors to the city include Spanish and Catalonian residents, professional and business MICE travellers, students and academics, sports players and fans, families and stag and hen parties, and people visiting their friends and relatives. The visitors are not homogenous, quite the contrary they go to different places and behave in a wide variety of ways, some “fit in” better than others.

Residents are impacted in different ways depending on where they live, near attractions or on tourist walking routes. Is there conflict over parking, noise and disturbance in residential areas? Is the problem over crowded public transport or rapidly rising housing costs? How exactly is tourism reducing the quality of life of residents? Which residents? What are the issues?

Elected representatives, surveys and local organizations can provide information and mobile phone data can reveal a great deal about visitor volumes and their movements around the destination.

The management adage, ‘you can’t manage what you can’t measure’, applies to the management of overtourism. Generally, we know too little. It is possible to count arrivals by air, road, rail and sea. Hotel and hostel occupancy can be monitored, private unregistered housing is more difficult to monitor and some will sleep on the beach or in parks. By scraping social media, it is possible to get big data results on what visitors like and dislike about the destination, indicating an agenda for action.

In my next post, I’ll discuss the wide variety of management interventions available to tackle overtourism.

Notes

-

Theilmann, J.M., 1987. Medieval pilgrims and the origins of tourism. Journal of Popular Culture, 20(4).

-

Ladić, Z., 2012. Criminal Behaviour by Pilgrims in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period.

-

Doxey, G.V. (1975) A Causation Theory of Visitor-Resident Irritants: Methodology and Research Inferences. 6th Annual Conference Proceedings of the Travel Research Association, San Diego, 8-11 September 1975, 195-198.

-

Butler, R.W., 1980. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 24(1), pp.5-12.

-

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3676849/Residents-baffled-coachloads-Chinese-tourists-descend-unremarkable-Oxfordshire-village-ask-selfies-told-used-HARRY-POTTER-films-rogue-tour-operator.html

-

https://responsibletourismpartnership.org/overtourism/

-

9 An, N. T., Phung, N. K., & Chau, T. B. (2008). Integrated coastal zone management in Vietnam: pattern and

perspectives. Journal of Water Resources and Environmental Engineering, 23